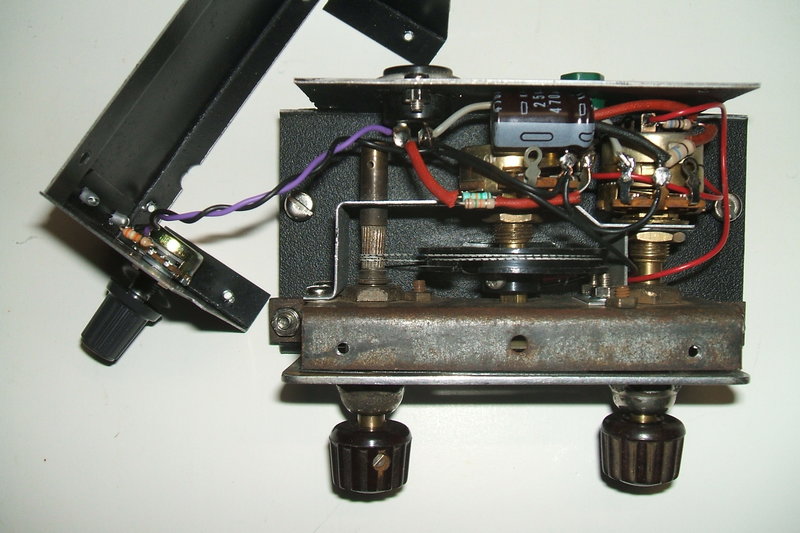

The receiver is used with a remote control unit and external speaker. The four pin socket to connect to the remote control can be seen here. Below are the speaker connections.

The receiver is used with a remote control unit and external speaker.

The four pin socket to connect to the remote control can be seen here.

Below are the speaker connections.

This is not the first radio to be installed

in my Model T. The original design was installed in the car just prior

to the Parkes trip, Easter 2004, and worked faultlessly. It was something

new and untried to have a radio in the Model T, so there was a lot to learn.

My original set was a hybrid design using a TDA7000 for the receiver and

valves for the audio. FM only reception was chosen because of the RFI caused

by the Model T ignition system. By mid 2006, I had enough experience with

this radio to make a few changes. For one thing, I was never really happy

about the solid state method of reception. While the TDA7000 works very

well, it was just out of place in a Model T. The new set would be all valve.

See the new set operating here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L6_U9xOBTns

The physical aspects of the set are based

on typical 1930's designs where all the circuitry is mounted in a box mounted

in a remote location, usually under a seat or on the firewall. The controls

are mounted on the dash or steering column, and operate the tuning condenser

and volume control in the receiver box via Bowden cables.

In the case of a 1926 Model T Ford, the

petrol tank occupies most of the behind dash space, so it is not practical

to mount the receiver there. The best location is therefore under the front

seat. With varicap diodes taking place of the tuning condenser, it is possible

in the modern day to eliminate the Bowden cables, and simply connect the

receiver to the remote control with ordinary wires. There is enough room

under the dash for a small remote control, or alternatively, the steering

column could be used. The remaining challenge is somewhere to put the speaker.

For convenience, and unobtrusiveness, I mounted it on the steering column

under the dash.

Limitations of a radio in the Model

T

First problem and one that can't really

be solved is the noise that one is subjected to in an open touring car.

The only way to deal with this is the brute force method; try and make

the radio louder. One thing that was immediately evident is that it is

a waste of time to achieve high fidelity sound. With all the noise present,

the lower level components in the audio signal aren't really heard anyway.

The other thing noted with the sound was that good bass response was pointless.

The low frequency components are masked by the rumbling of the engine.

The ignition system of a Model T is famed

for the RF interference it causes, and initially it was thought there might

be problems. This didn't turn out to be the case at all. Firstly this is

because the radio was VHF FM, and again what interference finds its way

into the radio is masked by the road and engine noise. So, that's a non

issue, unless you want Medium Wave AM. Even then from the experiments I

did try back in 2004, it seems that it might not be a lost cause. Bypass

condensers around the supply for the ignition coils might just improve

things.

The electrical system is a limiting factor

for the design of the radio. With only 5A available without discharging

the battery, the current consumption needs to be thought out carefully

and minimised. Unfortunately, this means being stuck with a single ended

output stage providing about 2.5W into the speaker. As much as I'd like

a push pull output or my 6CM5 amplifier (3.8W) the extra current required

is too much. It is true I could set the generator charge to a higher rate.

This would however overcharge the battery when the radio wasn't on, and

also the generator wear would be greater. The Model T uses a 3rd brush

type of generator which functions as a constant current source. There is

no voltage regulator. Charging current is set by the position of the 3rd

brush on the commutator.

The other limitations concerning radio

installation is where to put the radio. The under seat approach with a

remote control under the dash works very well. That aspect of the original

design would stay. The speaker position behind the steering column under

the dash is acoustically poor but physically convenient and out of sight.

A smaller speaker under the dash pointed at the occupants would probably

be better.

The speaker box is secured above the steering column with hose clamps.

This eliminates holes being drilled. The handbrake fully forward almost

touches the box.

The New Design

One of the things I wanted in the new

radio was a smaller remote control unit. Previously, this contained the

TDA7000 receiving circuit and a slide rule dial, and did look obvious,

much like a modern car radio. It was decided to move the receiver into

the main unit which would simplify, and miniaturise the remote control

unit. Additionally, this would tidy up the cabling, with the RG59 aerial

cable only having to go so far as the main unit under the seat, instead

of all the way up to the dash. Acquiring a small rectangular speaker that

could handle 2.5W with tolerable quality wasn't easy, so for now the idea

of speaker in the remote unit was overlooked and the existing speaker used.

Electrically, the new receiver wasn't going

to be much different to the previous, as far as audio and power supply

was concerned. However, the receiving circuit was now going to be my trusty

12AT7 super-regenerative receiver. No matter how well it works, the TDA7000

is a solid state IC and just seemed out of place in an 80 year old car.

The annoying thing I did find with the TDA7000 is how sharp the tuning

is. Even with the gearing down of the dial it was still critical and an

awful sound issued forth if the receiver was slightly off tune. With the

super-regenerative approach, the sound merely becomes more distorted as

tuning varies from the optimum setting. Using a super-regenerative detector

makes this an AM receiver (FM to AM conversion occurs by tuning the aerial

coil slightly off frequency; i.e., slope detection). This might be assumed

to be a problem so close to those four unsupressed ignition coils, but

not so. Firstly, there's less RFI at VHF, and also a super-regenerative

detector has inherent noise suppression. How? It's because detection actually

takes place only during the short periods when the detector builds up to

oscillation. The rest of the time anything received is ignored. It actually

acts as a sampling type of receiver, with the short samples fed into a

low pass filter to recreate the original modulation signal.

Obviously, with the new radio, tuning

would have to be done by varicap diodes controlled by a pot at the remote

control.

The remote control clamps to the lip under the dash avoiding having

to make any holes. Power / volume is on left. Tuning is on right. On the

extreme right side can just be seen the regeneration control. It seldom

needs adjustment.

As far as the audio section is concerned, there would be no negative feedback. The improvement in sound quality is totally wasted in this application. Additionally, it detracts from useful gain which is important when trying to minimise the amount of valves used. Furthermore, the frequency response would be concentrated with the mid and high range components. It's better to concentrate the power in the frequency range that can be heard above the engine noise.

The New Radio

Construction of the main unit chassis

and enclosure was virtually a copy of the original, as it was easy to construct

and served the purpose well. Layout was much the same too, but the height

of the cabinet was reduced as the original was a tight fit under the seat

cross member.

I also wanted the new radio to use the

existing wiring harness between the main unit, remote control, and speaker.

This meant six wires were available.

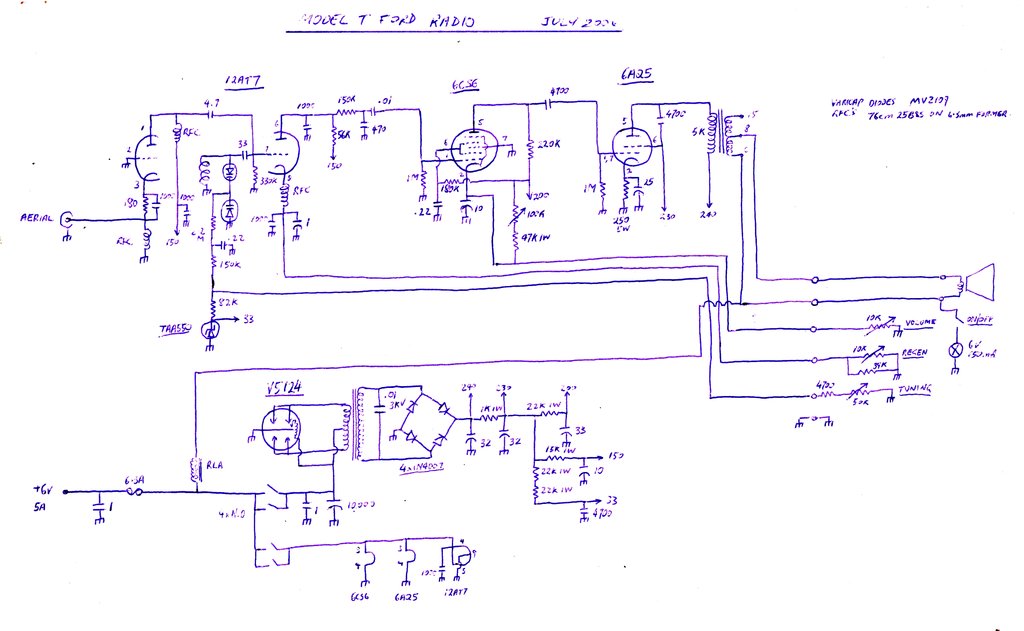

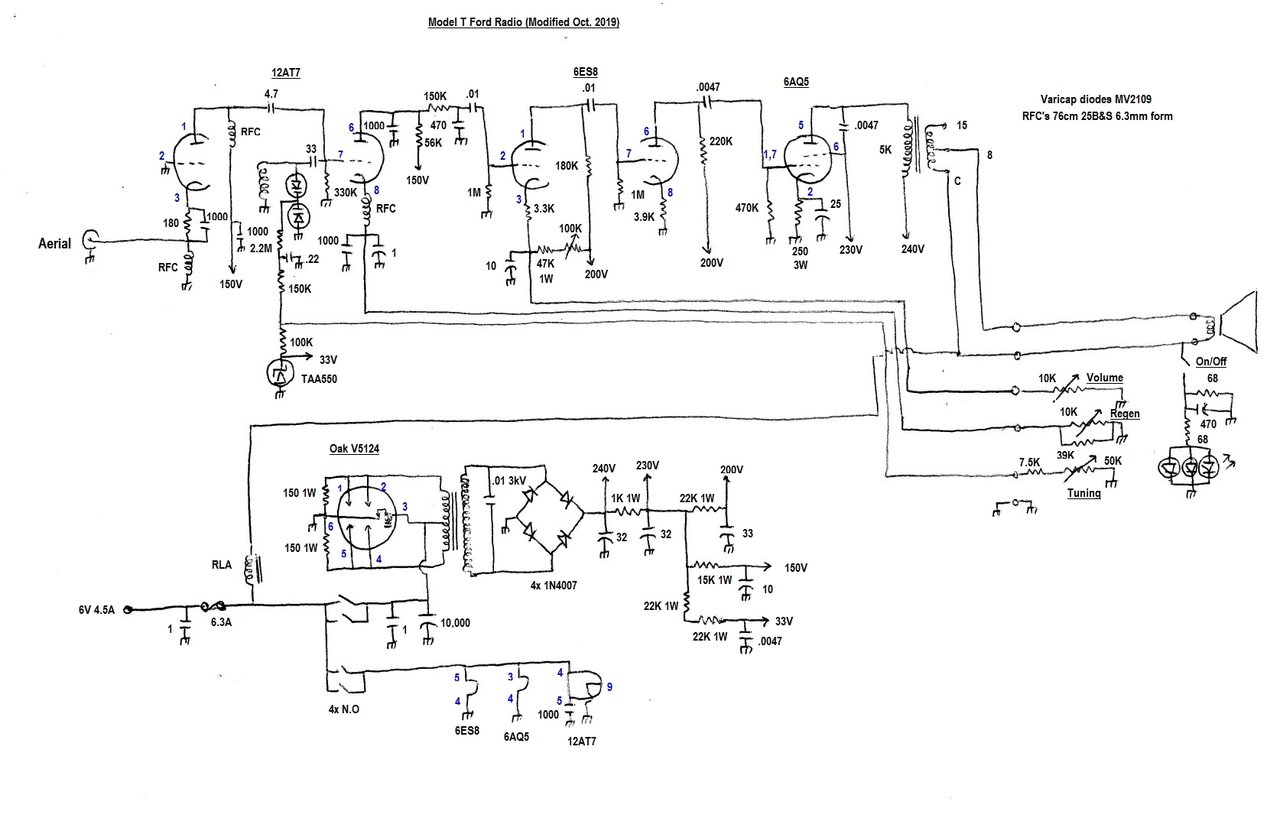

Let's now analyse the circuit:

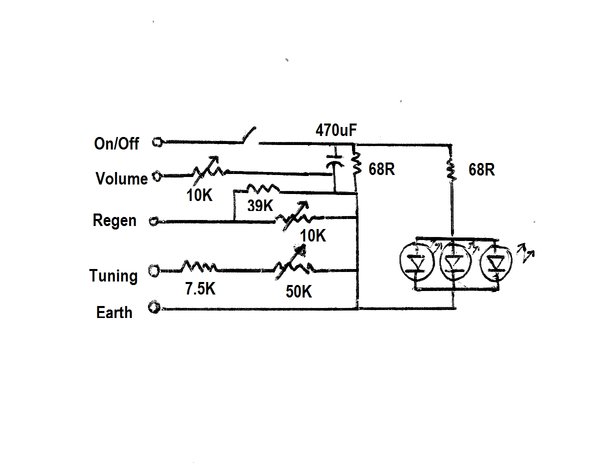

The circuit of the Model T Ford radio receiver. The remote

control unit circuit shown is for the original; it was altered later. Note

the freedom from unnecessary parts...much like the car itself.

Super-Regenerative Detector.

This 12AT7 circuit has been discussed

elsewhere on this site so I won't repeat it all, except to mention a few

slight differences. With the 15uH RFC's I'd been using up to now,

no longer available, I had to make them. They're of the same design as

used in the 6C4 receivers. 76cm of 25B&S wound over a 6.3mm plastic

former. While other 15uH chokes are available, they are of the axial type

and do not work in this circuit. The home made chokes actually are better

than the original 15uH ones and will allow the use of a 12AU7 instead of

a 12AT7. Regeneration control is by means of a cathode rheostat, but in

this receiver I've simplified the arrangement by not having any bleed current.

An advantage of this also is the current consumption is reduced. Remember,

the current consumption of anything drawing off the B+ is multiplied by

about 40 times as far as the six volt supply is concerned. The other reason

for doing this was to eliminate another wire in the cable up to the remote

unit. To do this means a higher value of pot than used previously. A 10K

pot turned out to be a good choice, shunted by a 39K to restrict the range.

Furthermore, the cathode rheostat, with no bleed current, actually provides

a degree of automatic regeneration control. The regeneration control, once

set, does not normally need further adjustment when tuning across the band.

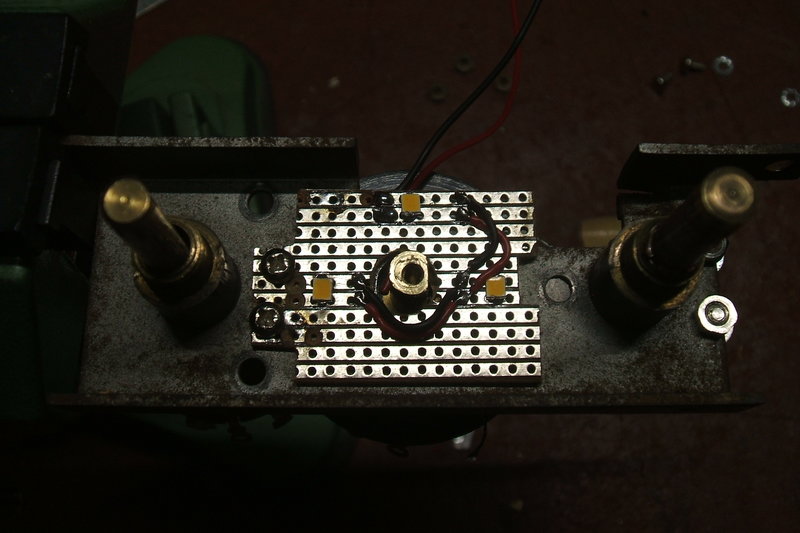

The receiver sub chassis undergoing testing and optimisation of

the circuit.

One interesting thing that had me confused

for a while was poor oscillation, especially at the 88Mc/s end of the band.

Nothing made sense. I'd isolated the RF amp in case that was loading the

detector. The circuit was checked. The chokes were identical to that in

the 6C4 receiver which has no problem in this regard. Then something occurred

to me...what if there was magnetic coupling between the cathode choke and

the

aerial coil and causing negative feedback. Then it wouldn't oscillate!

But why in this receiver?

What a trap this was...I looked at the

direction of the windings of both coils...took the choke out and reversed

it. What a difference! Good solid oscillation all over the band at last.

Tuning by DC

Short of using bowden cables linked to

a variable condenser, the tuning control had to use a potentiometer varying

a DC voltage. The obvious choice is to use varicap diodes for tuning and

here I ran into problems. As expected the Q was less than a variable condenser

and this prevented a 12AU7 being used. At first I tried a pair of BB105

diodes but couldn't get sufficient capacitance. Strange, as I'd used these

in my 12V pulse counting receiver with no problems. I then tried MV2109's

and at last was able to get the correct tuning range with a maximum reverse

voltage of about nine. The MV2109's also had much better Q as made evident

by stronger oscillation. One of the other worries about using varicaps

is the tuning voltage supply drift. Rather than use a zener diode, the

correct way is to use a special tuning voltage stabiliser IC, such as the

TAA550 or ZTK33. While these appear electrically as a zener diode, they

are constructed quite differently, and specifically designed to have good

temperature stability. The regulated voltage is approximately 33V. Again,

to simplify the wiring between units, the tuning pot is wired as a rheostat

and shunts the tuning voltage to earth. The combination of the 82K, 4.7K

and a 50K tuning pot provides the correct 88-108Mc/s coverage. The .22uF

simply shunts any noise to earth and any remaining RF at the supply end

of the 2.2M. Or so I thought. With the receiver up and running, I noticed

the volume setting had an effect on the tuning. Even with the volume control

wire disconnected at the receiver the effect was still there. Something

capacitive must be happening. The only other wire going into the wiring

harness was the tuning wire.

Well, despite the .22uF there must have

been RF flowing where it shouldn't. The 150K decoupler fixed that and now

the receiver was so much more docile and behaved just like it should.

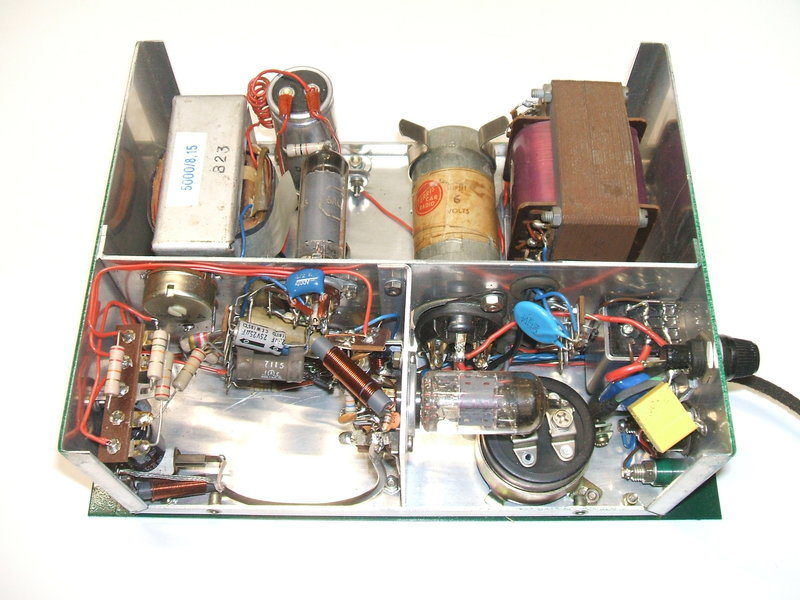

Close up of where most of the action is. The minimum volume preset

is upper left, with the power supply filtering components in front of it.

Two of the RFC's are visible along with the aerial coil towards the bottom

of the 12AT7 sub chassis. To the right is the 10,000uF electrolytic for

filtering the incoming 6v supply. The .01uF 3KV buffer condenser is clearly

visible behind the 12AT7.

The DC volume control.

This is a novel piece of circuitry I developed

for the original radio. Apart from requiring only one wire to control the

volume rather than three, any noise picked up on the wire would be shunted

to earth by a condenser, as we only want the DC voltage.

As before, I used a 6CS6, known in Europe

as EH90. It's a pentagrid valve similar to a 6BE6, and was popular for

TV use in Australia as a noise gated sync separator. By feeding a signal

into one of the control grids, the other control grid voltage will affect

the gain. In my circuit, an even better range of control is obtained

by varying the DC on both control grids. That is simply done by earthing

both grids (DC wise) and varying the cathode voltage. In case you are wondering

why I didn't use a 6BA6 or other remote cutoff pentode, it's because of

the range of control voltage required. The 6BA6 required about 30V to cut

it off; the 6CS6 about 16V. Why does this matter? Again, a rheostat wired

pot is used to control the volume. With the pot at minimum resistance,

the bleed current is fairly high in order to obtain 30V at max resistance;

compared to when only 16V is required. There's a preset 100K pot in the

main unit to set the bleed current, and therefore the minimum volume, when

the volume control is set to it's maximum 10K resistance.

The DC volume control works extremely

well. From a user point of view it is indistinguishable from the conventional

audio voltage divider type of circuit. Gain from this section also brings

up the detected audio level to drive the 6AQ5 output.

The power amplifier

This is a stock standard 6AQ5 output stage.

I kept to the 6AQ5 as it provides the most power output for the least heater

current, and I have a good collection of them. As mentioned before, no

feedback is applied. The input signal has the bass frequencies attenuated

by the .0047uF grid coupler. Realistically, the output power into the speaker

is about 2.5W which is typical for a cathode biassed 6AQ5 running off about

250V B+. Plate voltage is effectively lessened by the drop across the speaker

transformer and cathode resistor. One thing I was determined to do is use

a proper valve output transformer. Previously I'd used a 100V line transformer

which did a good job, but with not an exact impedance match, and interleaved

laminations, wasn't the most efficient thing to do. I decided on a chunky

Rola B23 transformer. The core looks like it could easily handle 10W. The

impedance ratio is 5000 to 15 ohms which is just right for a 6AQ5. It wasn't

right for the 8 ohm speaker however, so I simply unwound the secondary

and brought a tap out. I rewound the rest of the secondary back on so I'd

still have the option of using a 15 (or 16) ohm speaker in the future.

The power supply

No prizes for guessing I'd use a vibrator

power supply; after all that's part of the charm of a valve car radio.

I had hoped to use a synchronous vibrator in the normal self rectifying

circuit, but the only transformer I had for this purpose seemed to have

a strange characteristic or some sort of fault. It was a new old stock

transformer made by Astor. It was labelled as 6V which was what I needed,

and indeed when I built the radio up and used it, there was the 250V at

50mA I wanted. Alas, before the radio warmed up and was drawing B+ current,

the no load voltage was horrendously high. The secondary vibrator contacts

were arcing over, not only between themselves, but through the mica washers

in the base of the vibrator. The .01uF buffer condenser rated at 3KV eventually

went up in smoke! This transformer was obviously a lost cause, so the next

in turn to try was a mains transformer, with a secondary I'd rewound to

give a suitable turns ratio for 6 to 250V vibrator use. It was a Telefunken

transformer that looked like it was from the 1960's. I have no idea what

it was out of, with a secondary voltage of about 7 and tapping of about

3.8V. Conveniently, this was rather close to what I needed, and the core

size and wire gauge looked perfect for what I wanted. As it was, despite

the uneven "centre tap" I powered up the transformer from a vibrator and

it worked quite well. However, this winding now functioning as the primary

was contributing to DC through the core with the asymmetrical tapping.

It would have been tolerable if necessary, but I did the right thing and

rewound it, bringing up the efficiency by a worthwhile amount.

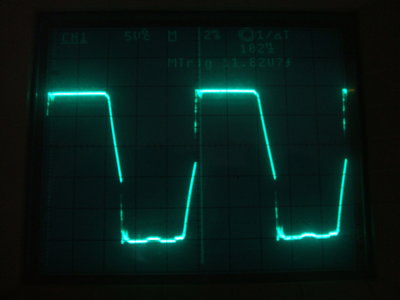

Vibrator waveform is text book quality.

I like the idea of a self rectifying synchronous

vibrator, but alas with a single 250V winding it wasn't going to happen

in this radio. So, in with the 1N4007's. Not quite keeping in with the

theme but they work well, and are reliable with the high unloaded voltages

from a vibrator supply. Schemes involving valve rectifiers were ruled out

given the extra current consumption. I retained the synchronous vibrator,

and simply paralleled the primary and secondary contacts to convert it

to non synchronous operation. The vibrator is an Oak V5124.

On the six volt side of things, the heaters

and inverter are switched by a relay. This is done to eliminate the stress

on the power switch contacts. It also eliminates another wire to the remote

control unit, as the radio is turned on by earthing only one wire. Incidentally,

to keep down on the wiring between units, the switch wire is common with

one of the speaker wires.

The incandescent dial lamp of the original

control head was actually in series with the relay coil. This eliminates

the extra current consumption that would come from simply wiring the dial

lamp across the 6V supply.

It may be thought that a 6V relay would

not function with so much voltage dropped across the lamp (about 3V). It

works perfectly, making use of two well known properties about both components.

Firstly, an incandescent lamp has a low filament resistance when cold;

i.e., soon as the radio is switched on. Secondly, the holding current required

for a relay coil is a fraction of that required to pull it in. So when

turned on, the relay receives pretty much full current. The lamp warms

up in less than a second by which time the relay has pulled in.

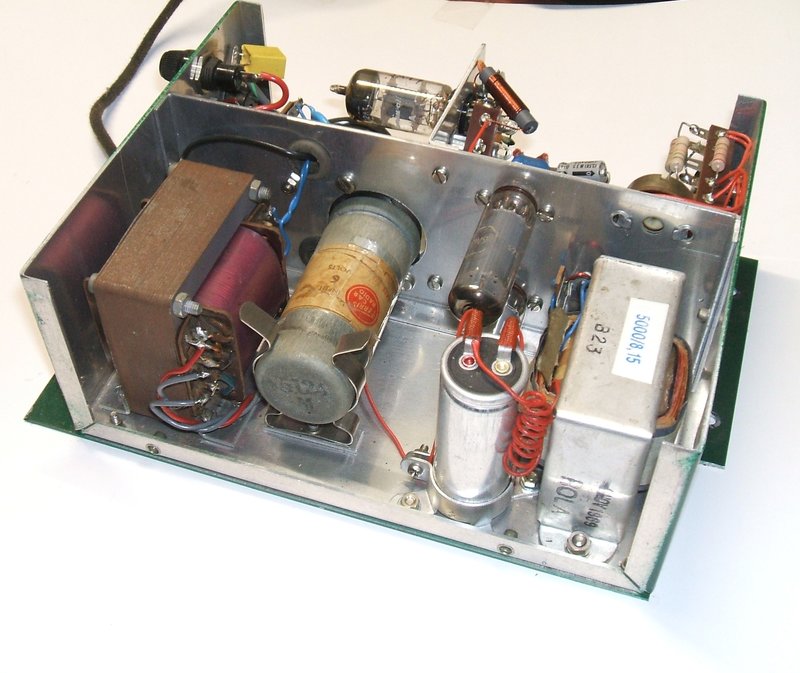

The finished radio. The 6AQ5 is between the vibrator and speaker

transformer, with the 6CS6 beneath it. Note the size of the speaker

transformer to right of the 6AQ5.

Wiring and components can be seen from this side. At the left is

the super-regenerative detector and audio circuitry. At the right is the

power supply.

Much to my delight, the vibrator interference

was easy to eliminate. First thing was to add the 10,000uF condenser right

at the vibrator socket. Car radio manufacturers would have loved such high

values back in the 1950's! This eliminated most of it, but being a perfectionist

I tried connecting a 1uF polyester against parts of the 6V supply and found

another chunk of noise gone at the relay contacts. The last of it disappeared

with another 1uF (the yellow thing in the pic above) from the fuseholder

to earth. Elimination of vibrator interference is really an art. You can't

tell the steps needed until the radio has actually been built.

After all this, the radio was putting

on a really impressive performance, working as well as a mains powered

unit. The case was etch primed and painted in green enamel. Installed in

the car with the existing aerial there was no doubt about the sensitivity,

with 2ST from the southern highlands coming in better than it does with

most receivers.

The radio fits under the front seat. The black box to the right

is a 6 to 12v converter used to power appliances such as a car fridge and

air compressor.

Remote Control Unit.

Originally as the radio was built in 2006,

I used a 10 turn pot for tuning. The intention was to eventually build

a remote control with a proper vintage looking dial.

Original control unit while functional did not look antiquated enough.

Also, the dial was hard to read while driving.

Inside the original remote control unit. From left to right is the

on/off volume control, ten turn tuning pot, dial lamp, and to the

side is the regeneration control.

The original worked well, but always looked

out of place. In 2019, a control unit from a Ferris model 56 turned up

in a box of junk at the HRSA. Realistically, a complete 56 isn't likely

to turn up (as much as I'd like one) so it was decided to rebuild the control

unit for the Model T radio.

As the 56 was produced from 1938 to 1939,

the dial and surround has an art deco appearance, and looks the part for

the Model T. As with all such units, the control head operated the radio

via bowden cables. To use it with the Model T radio would entail removing

everything but the actual dial, and fitting potentiometers instead. Also,

the existing 6.3V dial lamp would not be suitable.

The rebuild was extensive, with a lot

of intricate metal work and brackets to be made up.

Inside the rebuilt Ferris control unit.

The tuning potentiometer had to have the shaft drilled and tapped to take the dial pointer. The existing dial drum was not suitable, so a plastic one had to be used. It is of larger diameter, which meant the enclosure for the whole thing would no longer fit. A larger enclosure was made up. A bracket had to be made to support the volume and tuning pots. The existing dial pulley was used. The regeneration pot was mounted at the side of the enclosure.

Control unit is clamped to the lip under the dash without drilling

any holes.

As far as the tuning and volume controls were concerned, these were the same as the original control unit, except that the resistor in series with the tuning pot needed to be increased from 4.7K to 7.5K. This was because there was too much below band coverage.

Circuit of the new remote control. Speaker connections not shown,

but one is common with the on/off control as previously.

The regeneration control also remained the same, with a 39K resistor to reduce the amount of dead spot with the 10K pot. The dial lamps were the next challenge. Now the dial actually had to be illuminated. In the previous remote control, the dial lamp was merely a power on indicator, which glowed at less than half brilliance. Because of the dial lamp having to be in series with the relay coil, options are limited. With only about 50mA available, it would be difficult to use an incandescent lamp and light the whole dial. Therefore, it was decided to use LED's.

Three SMD LED's provide dial illumination.

Three warm white surface mount LED's were obtained from a burnt out 240V light bulb. They were mounted on a piece of Verobard behind the dial. This worked exceptionally well, and only a few mA were needed to give bright illumination. Next was to modify the on/off circuit to operate with the LED's. With no more incandescent bulb providing an initial low resistance in series with the relay, a 470uF capacitor was used instead. It was found for reliable relay operation, that the maximum resistance in series along with the 470uF, was 68R. This allowed about 3.6V for the LED's which was perfect. Next was the LED series resistor. While it's not the best way to do things, the three LED's were connected in parallel, and the current sharing seemed even enough, with equal brightness. In series with the LED's the current limiting resistor was 68R to give a sufficient brightness to see that the radio is switched on in daylight. In the dark the brightness is perhaps more than required, and thoughts are to use an LDR to automatically reduce brightness.

Dial lamps appear brighter than they are due to the camera.

The final part of construction was the

dial "glass". There was none present when I got the control, and it would

have been a piece of celluloid. I had ideas of using a piece of Lexan,

but the thinnest piece I had was still too thick for the panel nuts to

grip the control shaft surrounds.

I simply used a piece of plastic cut from

some packaging. It has perfect transparency, is thin enough, yet stiff

enough to protect the dial. In fact, the kind of plastic used is very similar

to the original celluloid.

The Aerial.

Aerial is a 75cm brass rod.

The aerial is a 75cm brass rod attached

to a PL-259 plug. It is supported in the plug body, and insulated from

it by a piece of plastic rod turned down to suit. This bites into the thread

of the plug body making a very secure attachment.

The PL-259 plug is then attached

to a panel mount joiner, which is mounted on a Marvi-Plate bracket secured

to the number plate mounting. From the other end of the joiner, the RG-59

coaxial cable connects via another PL-259 plug. The coax was shrouded in

black shoe lace to give it the vintage appearance.

Close up of how the aerial is mounted.

Improved circuit to obtain more volume.

To improve on this would entail adding

some extra gain between the DC volume control stage and the 6AQ5. Simpy

adding an extra triode valve would be a logical start, but there was nowhere

to accomodate it. Either the 6AQ5 or 6CS6 would have to be replaced by

a dual valve. It would be easiest to replace the 6AQ5 with a triode pentode.

The 6BM8 would be ideal, except its power output is not as high as the

6AQ5, and in this application a reduction of this would defeat the whole

excercise. 6GW8 would be a possibility, but being a high gain valve, I'm

not convinced it would be reliable in the long term with regards to vibration.

It's also a valve I don't have a huge quantity of, and the audiophile crowd

have pushed its price up if buying new.

For the operating conditions, 6AQ5 remains

the best choice, particularly with regards its relatively low heater current.

Replacing the 6CS6 with something of higher

gain was the first experiment. The 6CS6 stage provided a gain of 117 times.

Whilst browsing the RCA Tube Manual, I noticed in their tables of RC amplifier

specs, that 6CB6 was mentioned. This was interesting because normally this

valve is known for RF applications. For the DC volume control circuit,

it was actually plug in compatible, and all that needed to be done was

to change the screen resistor to 680K. Results looked very good at first.

Gain was 264 times, and the 6AQ5 could be fully driven under all circumstances.

Unfortunately, the problem of using a

sharp cut off valve became obvious. With a strong signal coming from the

12AT7, and with the volume set low, the distortion was unacceptable. This

is because when the valve is close to cut off, it's working in class B.

That is, the postive cycle of the input signal is amplified more greatly

than the negative cycle.

Type 6BZ6 is a semi-remote cut off version

of the 6CB6. This was a lot better and almost passable. Alas, the distortion

was still sometimes evident. While I did not actually measure the gain,

I did notice that the 6AQ5 could not always be fully driven.

One difficulty with modifying this stage was the 7 pin valve socket. This limited the valve to being a single pentode or triode. That is, except for the 6J6 twin triode. If both triodes could be utilised, suitably high gain might be obtainable. The catch is, the 6J6 has a common cathode. This would cause difficulty since the cathode voltage varies with the volume control setting. Nevertheless, it was found that one 6J6 triode worked quite well as a DC volume control without obvious distortion. Attempting to use the second triode to increase the gain wasn't successful because of the cathode coupling. At this point, it was clear the 7 pin socket would have to be changed to a 9 pin type to allow the use of a valve with separate cathodes.

This wasn't a simple matter, because of where the 6CS6 was located, at the bottom the upright chassis. It would be impossible to get a socket punch or cone cutter in to enlarge the hole. Another option was to move the 6AQ5 to where the 6CS6 had been, and put the 9 pin socket where the 6AQ5 was. This was easily done and the 9 pin socket was installed.

First valve I tried was a 12AX7, as this is the highest gain of twin triodes. Alas, the sharp cut off characteristic was severe. Remembering the 6J6 worked OK, I thought that a lower gain triode should have a better control characteristic. And, so a 12AU7 was tried. This was looking good! Alas, the gain with both triodes in operation was only 114 times; no better than the 6CS6 it was replacing. In view of this, the 6J6 wouldn't have had enough gain even if it could be made to work.

What was needed was a kind of combined

12AX7/12AU7; a twin triode with one section being low gain for the volume

control, and the other being high gain to drive the 6AQ5. Such valves are

not common types, so this idea was immediately discounted.

What about a triode pentode? The 6BL8

has a triode not too dissimilar to a 12AU7, so that was tried next. Things

were looking really good now. A gain of 450 times was more than enough,

and the control characteristic seemed good. Unfortunately, closer observation

revealed all was not in fact well. Even with no cathode bypassing, the

gain was actually too high. At high volume, feedback was evident. A high

frequency oscillation could be heard. Capacitive bypassing didn't get rid

of it, and it was only evident when the super-regenerative detector was

operating. I wondered if it was because the 6AQ5 socket was now close

to the tuned circuit, and there was some capacitive feedback. A small sheild

was made up and placed between the tuned circuit and the 6AQ5 socket and

this seemed to improve things. It still didn't completely get rid of it.

On a few stations it was also noticeable that the distortion was still

there at low volume.

Now it was looking like I'd have to go

back to a 6CS6 kind of circuit, using a pentagrid or similar, to eliminate

the distortion. There were some Philips 10 pin valves introduced in the

1960's for TV use. Type 6V9 was of potential interest as it contains a

triode and a dual control heptode. The 10 pin (Decal) socket fits the same

hole as the 9 pin type. Whilst browsing through one of my Miniwatt

booklets to look at the 6V9 data, I glanced upon the the fact that type

6ES8 is actually a semi-remote cut off type. This is a frame grid twin

triode, intended for cascode VHF amplifier circuits. Before changing the

socket to take a 6V9, I thought I'd just give the 6ES8 a try.

This worked surprisingly well in fact.

With both triodes in circuit, gain wasn't high enough to cause problems

like it did with the 6BL8, and the control characteristic was good. Certainly,

keeping in mind this is not a hi-fi receiver, the distortion at low volume

is not problematic.

Note the small shield near the tuned circuit tagstrip.

One final modification was done and that was simply to add 150 ohm resistors across the vibrator contacts. While the vibrator has been completely reliable over the 13 years this receiver has been in use, inclusion of these resistors is the right thing to do. Also, the 6AQ5 grid resistor was replaced with 470K in line with specifications.

An interesting discovery was made regarding the 82K resistor in series with the tuning control. While rearranging parts on the same tagstrip, I noticed I had used a second hand carbon resistor. Not surprisingly, when I measured it, the value was 105K. Suspicious that this might be contributing to the tuning drift this receiver has always had, I heated it with a soldering iron, and sure enough the resistance increased. I replaced it with a new metal film 100K and the drift became less evident.

6AQ5 where the 6CS6 was, and 6ES8 where the 6AQ5 was.

While the improvement in gain has been

worthwhile, audio output is ultimately limited by the single ended 6AQ5.

Before distortion sets in, power to the speaker voice coil is only 1.5W.

There is no way to increase it, but to use a push pull output, or a larger

valve like 6L6 or 807. This would increase the current drain of the radio

to the point of the battery actually discharging.

A push-pull stage using two 6AQ5's was

subsequently built up for the radio. It increased the audio power to just

over 5W. See

here for the details.