Low voltage B+ receiver and amplifier circuits using mains type valves have been described elsewhere on the site. This article looks at the use of low B+ with battery type valves, used in one valve receiver circuits.

One valve regenerative receivers using a 1Q5 were a popular project, because good results could be obtained with only 9V B+. Not only did this make for a more compact set, but one that was considerably cheaper to operate than one requiring a 45V battery. Such sets were popular with campers and hikers.

Hiker's One.

In fact, the whole background of the design

comes from a circuit, known in this part of the world as the "Hiker's One".

The circuit was first presented in QST for October 1935, and was a two

valve receiver with a 49 operating as a regenerative detector in space

charge mode, and a 30 operating as an audio amplifier in the normal way.

From QST, October 1935. This appears to be the first recorded use

of the 49 in space charge mode.

A modified version of the circuit, without

the audio stage, was presented as a constructional article by Popular Mechanics

for September 1936, its claim to fame was that only six 1.5V cells were

required to power the whole set.

From Popular Mechanics, September 1936. For the original article

see https://archive.org/details/PopularMechanics1936/Popular_Mechanics_01_1936/

Besides the low B+ voltage, the other novel

feature was the use of the rather unusual type 49 valve. By operating this

so called 'dual grid' valve in space charge mode, enough plate current

would flow at 6V for the circuit to function. In simple terms, taking the

first grid positive forces sufficient electron flow to occur at the lower

than normal voltage. The signal is fed into the second grid, and the valve

functions as a triode. The 49 is an obscure type which I have never seen

in any commercially made equipment, let alone any circuit diagrams for

such.

In this part of the world, the Popular

Mechanics circuit was promoted by the Lamphouse in Wellington, NZ. They

gave it the "Hiker's" name and sold it in kit form. The circuit was slightly

modified to become the "Improved Hiker's", and was a very popular kit.

In fact, one valve receivers were always popular in Australia and NZ, right

up until the transistor era. We didn't have the affluence of the middle

class U.S., and radio components were expensive. Such receivers built in

a compact portable form also suited our outdoor lifestyle.

I have never seen the 49 circuit in any Australian publication of the period, which was no doubt due to a preference for locally made valve types, of which the 49 was not. Australian designed one valve sets were of more conventional design, including the very popular 19 or 1J6 circuit, which also appeared to have originated in the U.S. That circuit was known here as the "Little Jim"; the name given to it by the "Wireless Weekly" magazine. My version can be seen here.

A compilation of articles on the Hiker's One can be seen at another site here.

Release notes from AWV, July 1939. At right is the equivalent Philips

DL36.

Since the 1Q5 is designed for a relatively high cathode current (11.1mA) at 90V, it could be imagined that when used as a regenerative detector, only requiring a fraction of a milliamp, that operation at lower voltage should be possible. Indeed, good performance was obtained with only 9V, and the Hiker's circuit lived on with its economical B+ supply. Type 1C5 is similar, though less sensitive, and was also recommended for the circuit.

Other 9V HT Receivers.

"Radio & Hobbies in Australia" presented

a 1Q5 receiver design in July 1946. It was shown using a size D cell for

the filament, and a multi-tapped 9V C battery for the B+.

From Radio & Hobbies, July 1946. Coil data is given at right.

Coil former is 1.25"

Both Radio & Hobbies and the Lamphouse also presented two valve versions of their 9V sets, using another 1Q5, 1C5, or 49 as an audio amplifier.

Once miniature output valves became available, there was no reason not to use them. The following circuit uses a 1S4.

From the Lamphouse 1948-1949, this circuit uses a 1S4. One wonders

if performance might be improved by connecting the 1S4 as a pentode, rather

than as a triode.

Radio & Hobbies used the 3S4 in a circuit with a variable capacitor for regeneration control.

From Radio & Hobbies, December 1952, this set was part of an

instructional series, starting from a crystal set and ending up as a three

valve portable.

Although it wasn't exactly 9V, the final low voltage B+ one valve circuit presented by Radio & Hobbies was in September 1954.

From Radio & Hobbies, September 1954, this set used a 30 triode

with 13.5V B+ obtained from three 4.5V cycle lamp batteries.

The well known radio historian, Peter Lankshear,

wrote an article on the Hiker's One in "Electronics Australia", October

1989.

Peter Lankshear's Hiker's One uses a 49.

The HRSA "Radio Waves" magazine presented articles on the Hiker's circuit for January, April, and July of 2008. A short form kit was available with a choice of 49, 1Q5, 3Q5, or 3V4 valves. The set was intended to be used as a portable with a loop aerial, and included an LM386 audio amplifier IC.

Portable loop aerial version uses IC amplifier.

1. The Cabinet Set.

Pictured at the beginning of this article,

this set was completely enclosed in a wooden cabinet, fitted with a handle.

The cabinet has been made from the wood of a butter box, the origin of

which seems to be from the town of Lyttelton, in NZ's South Island, from

the printing on the inside.

Inside the cabinet version.

The tuning capacitor is a rather ancient Stewart Warner, complete with 0-100 dial. It was once fitted with a reduction drive, but the drive gear has been removed. The tuning knob attaches directly to the shaft. The other controls are a rotary on/off switch, and the regeneration control potentiometer. A primitive battery holder for two D cells had been made up on the back of the chassis. Battery holders, as we know them today, were virtually non existent as an individual component available for purchase. There is space at the side of the chassis for the 9V battery. An English made Philips DL36 had been fitted.

Under the chassis. For a simple MW set like this, a wooden chassis

is acceptable.

The DL36 had suffered a common fault with

the style of valve construction used. Some octal valves did not have a

full bakelite base, but had just the pins in a bakelite moulding. The glass

was secured to this via a metal ring (see pic above of the DL36). The metal

ring often splits, which is what had happened here. The valve was flopping

about on its wires, which fortunately had not broken off. It was an easy

repair, just a length of tape around the ring holding it all back together.

And I'm pleased to say the valve itself was undamaged.

Since the valve socket is below the chassis,

and with the thickness of the wood, the valve cannot be fully seated. In

fact, the valve was just about to fall out when I got the set.

A nice thing about sets like this is they'll

usually work straight away. With only 9V, one does not have to worry about

replacing leaky paper condensers (not that there are any). With only one

resistor, whose value is not critical, this doesn't even need checking.

And so it was, with two D cells put in

the holder, and 9V from a bench supply, the set worked straight away.

In fact, I'd forgotten just how well this

design works. It was late afternoon, and the distant stations were starting

to come in at good strength. After sunset, my 'sensitivity test station';

Newstalk ZB from Wellington was coming in (2ZB 1035kHz 50kW). Distance

is about 2200km. The regeneration control worked as smoothly as one could

wish, and even with no vernier control, there was no difficulty tuning

between stations.

One odd thing I'd noticed was that the 9V supply wires had been extended through holes in the cabinet. It is curious why this was done, since there's plenty of room inside the cabinet for a battery. In the modern day, a 216 type 9V battery is a logical choice, although a set of six AA cells is more keeping in with the period theme. Also appropriate would be two 4.5V cycle lamp batteries, but these are now difficult to obtain.

Headphone terminals are on the front panel.

The second set looked suspiciously like

a Lamphouse kit, although a closer look shows that it is not. The parts

layout is much the same, as is the row of Fahenstock terminals along the

back of the chassis. However, there are fewer terminals, and the circuit

is slightly different. The function of each terminal has been stamped into

the wood which definitely supports the 'it was a kit' theory.

The control label logos suggest SOS Radio,

another kitset supplier.

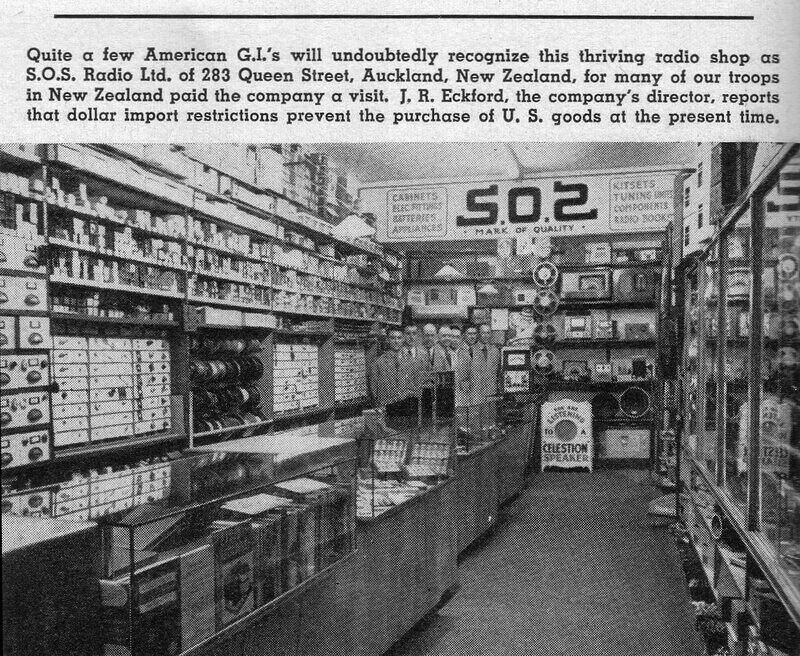

S.O.S. Radio mentioned in "Radio & Television News", March 1951.

In this set, the variable condenser is an English "Polar" type. Instead of the separate switch and pot, a combined switch pot is used. The components are more modern, being from the early 1950's, with PVC wire, a more modern grid resistor, and mica capacitors. The valve fitted is another English made Philips DL36. Two of the Fahenstock terminals had broken, but luckily I had replacements.

When it came to testing this set, results

were very different. It was not possible to reduce the regeneration sufficiently

unless the B+ was reduced to 8V.

At this point, I hadn't actually traced

out the circuit, and had just assumed it was the same as the Radio &

Hobbies design, since the pot was clearly marked 500k, which would imply

screen grid control. At a glance, both sets appeared to be using

the same circuit, so why the difference?

From the 1950-51 Lamphouse catalog. Looks the same doesn't it? A

closer looks reveals subtle differences.

The open chassis set's physical appearance mimics the Lamphouse design, but on closer looking at the actual Lamphouse circuit, the 1Q5 operates in space charge mode, with +1.5V on grid 1, and the signal fed into grid 2. However, both sets I have use the conventional tetrode connections, with the signal fed into grid 1 and the 9V supply fed to grid 2.

Circuit of both sets. The regeneration pot value is 10k for the

cabinet set, and was 500k for the open chassis set. It is now 2.5k.

Regeneration Control.

The set built in the cabinet worked perfectly

and did not need any work. The question was with the open chassis set;

what to do about the regeneration control. The pot in the cabinet set was

not labelled, so I measured it and found it to be 14.6k. It would appear

it was a 10k type which had drifted. 5k to 50k is typical of the value

used for shunt control, so all was good here. No wonder control was poor

with the open chassis set, with its 500k pot. As it was, the control action

was cramped at one end, with most of the pot travel doing nothing. A further

complication arises with switch pots, in that the lowest minimum resistance

is higher than a normal pot, unless the carbon track has been specifically

designed for such use. The reason for this is because of the wiper travel

before the switch actually turns on. Incidentally, switch pots tend to

wear out faster, since every time the set is switched on or off, the wiper

moves over the carbon track. With a separate switch, the potentiometer

will usually be left in much the same position.

Using the 500k Pot.

With 9V B+, the minimum resistance of

the pot was too high. Seeing as the pot was 500k, it seemed logical to

convert the circuit to the R&H design. I must admit an element of surprise

when I had a closer look at their circuit. In previous times when I had

glanced upon this circuit, I just thought the 250k pot was in series with

the screen grid. But looking closer, we see the screen is fixed at 9V,

and the pot varies the plate voltage instead. It's an unusual way to do

things. R&H's theory was that fixing the screen at 9V would ensure

the greatest electron flow for the low plate voltage. I tried it, and it

certainly gave very smooth control, but soon became aware of a serious

problem. Below a certain plate voltage, the signal suddenly dropped off

in volume and became very distorted.

If the optimum regeneration setting was

above this point, all was good and it worked well. But, if it was necessary

to go below this point to get it to stop oscillating, it was unsatisfactory.

One possibility is the aerial connected to the R&H lab was of sufficient

length to load down the tuned circuit, so that their set was always operated

above this point. Also there is a slight difference in the R&H coil

specifications, compared to those in the receivers at hand. The R&H

set used a commercially made Reinartz coil, but details were provided for

those who wanted to wind their own.

Why did my own construction of the set

ca. 2000 not have this problem? I'm very certain I had wired the set for

screen grid control. And so, this is what I tried next. The 500k pot was

connected in series with the screen and bypassed with a 0.1uF condenser.

This worked very well with a perfectly smooth control.

There is one possible disadvantage with

screen grid control. That is, since the gain of the valve is affected by

the screen grid voltage, the gain will always have to be lower than what

it could be, in order to back off the regeneration to the point just below

oscillation. This is not problematic with circuits operating with conventional

B+ of greater than 45V, since the gain is already more than enough. But

with only 9V, when we're trying to get every bit out of the valve, it could

be. Fortunately, this did not turn out to be so, since the optimum screen

voltage was around 7.5V, and gain was still ample.

Connecting the 500k pot as a rheostat in

series with the screen seemed like the answer. One characteristic of the

rheostat connection is that the volume cannot be reduced to nothing. With

the low volume level of a one valve set, this is not a problem, but I tried

using the pot as a voltage divider. This gave complete control as expected,

but would be unsuitable for this particular set, since there's only one

set of switch contacts. This means there's a 500k load across the 9V battery

even with the set switched off. Ether a rheostat connection has to be used,

or a double pole switch fitted.

The 500k pot works well as a screen grid control.

I was happy with the rheostat connection,

but before implementing it, I thought I'd have a look through my switch

pots and see what I had in the way of lower values, so as to retain shunt

control and keep the original wiring.

25k was tried and worked acceptably, although

the control was cramped at one end. I found a 2.5k pot which worked very

well. It seems the optimum shunt resistance is around 1k, so the 2.5k pot

is ideal. I installed it permanently.

In comparison to the screen grid control,

there's very little to choose between how the set performs. There was no

obvious change in sensitivity and volume.

The question remains as to why a 500k pot was originally used in this set as a shunt control. I can only put this down to the fact that the most easily available switch pot was the 500k type, since this is the standard value of volume control in valve circuits. The original Popular Mechanics circuit uses 500k, and this was duplicated in the Lamphouse version. 500k just doesn't seem right, since the regeneration coil is a low impedance circuit, and it's interesting to note the 10k pot in the cabinet version, and also the more recent HRSA circuit, as shown previously. Lower resistance volume controls did not become common until the transistor era. (5k and 10k volume controls were common in 1930's sets, but they didn't usually include a switch). The B+ terminal is clearly labelled as 9V, so it is a mystery how the constructor of this set was able to use it.

Headphones.

This kind of set was intended to be used

with high impedance headphones, of the type that go right back to the beginning

of radio. Typically, these have a resistance of 2000 ohms.

High impedance phones like this were used with crystal and one and

two valve sets.

Unfortunately, they are very uncomfortable with the hard bakelite earpieces, and the sound quality is rather poor. Much better results can be obtained with modern stereo headphones and a matching transformer.

Modern headphones with transformer matching are a far superior substitute.

Although high impedance headphones are

usually quoted as being "2000 ohms", this is the DC resistance. The impedance

(AC resistance) is a lot higher, by approximately 10 times. So, to use

modern phones, the transformer needs to reflect an impedance of at least

20k. The best type of transformer to use is a multi-tapped 100V type used

for public address systems. The primary impedances are not usually quoted,

but the input power levels are. From that, the impedances can be calculated.

See here for further

details.

With the 1Q5 sets, the 30k tapping provided

the loudest volume, equal to the high impedance phones. The 20k tap was

almost as good, but the volume dropped off considerably with lower impedances.

B+ current is around 280uA, so even a small

9V type 216 battery is practical. Filament current is 100mA, which is probably

best obtained from an alkaline D cell. Since these have about 20Ah capacity,

about 200 hours operation should be possible. I am very wary of running

battery valve filaments off a bench power supply, since the possibility

of an accident is too great. Battery valves won't survive an overload,

no matter how momentary.

Testing circuits with battery valves needs

to be done with utmost care. There are many sad tales of a whole set of

valves blown when the B+ got mixed up with the filament circuit.

For this reason, during the testing of

these two sets, I used a bench power supply for the B+ only, with the current

limit set to only a few mA. This way, the 100mA filament of the 1Q5 could

not be damaged in error. It is worth noting also, that filament continuity

checks on battery valves using a multimeter can cause damage. If the multimeter

uses anything more than a 1.5V cell for its ohms range, it's possible for

high enough current, particularly on the low ohms range, to pass through

the filament and destroy it. Use a high ohms range if testing filaments.

One other aspect to be aware of, for those

not familiar with battery valves, is that the glowing filaments are barely

visible, if at all. Do not expect them to light up in the same way as mains

type valves do.

The parts to build this set are all standard, although of course the tuning condenser will be the most difficult to get, if buying new. Nevertheless, they are available from a few suppliers, such as Antique Electronic Supply.

According to the Lamphouse specifications, the coil is wound with 32 gauge enamelled copper wire on a 1.5" diameter former. In the modern day, PVC pipe or conduit makes a good former. Regeneration is 40 turns, grid 100 turns, aerial 35 turns. Spacing between each winding is 1/16". Windings phased as per the circuit diagram. There is a slight difference in coil spacings with the two sets described, but it is not super critical. The less spacing, the tighter the coupling, and vice versa. There is some room for experiment here.

Chinese Hiker's One kits. Modified version on left.

For sale via the usual sources of such things, eBay and AliExpress, are various kit radios from China using valves. Among them are several variations of the Hiker's One design using a 2P2 battery valve. Other sets have two or three valves, with some covering the SW bands. There is also a super-regenerative kit for VHF using one or two valves.

Circuit of the 2P2 receiver. There are some minor variations between

circuits.

A ferrite loopstick is supplied with these

kits instead of an older style air cored coil. These are still being made,

and thus easier to supply. It's possible to use the radio in a strong signal

area without an external aerial.

The 2P2 is equivalent to a 3S4, which

being a battery output valve, should work in the same manner as a 1Q5.

As with the original 1Q5 circuit, only 9V B+ is required.

Schematically, the only difference with the 2P2 circuit is the regeneration control. Instead of a variable shunt across the regeneration winding, the potentiometer varies the amount of bypassing to earth. Consider the pot wiper to be in the upper most position. The full 10k resistance is across the winding, and the wiper connects the 2000pF bypass to the output transformer plate connection. Thus, regeneration takes place, since the full winding is in circuit. Now, consider when the pot wiper is at the lowest setting. The 2000pF bypasses the 2P2 plate to earth, so that none of the RF on the plate reaches the winding. There is then no regeneration.

There are some slight variations with the

actual circuit. The particular examples I have don't include the high impedance

headphone socket. The grid capacitor is 240pF, and the tuning capacitor

measured 278pF. C3 is 2200pF. These are not critical values.

Also, there is some difference with the

battery connections. The 1.5V positive connects to pins 1 and 7, and the

negative connects to earth via the switch. The 9V negative returns to the

1.5V positive, thus giving 10.5V for the B+.

Construction of the set is on a pine board

with a plastic panel; the latter designed to be used with several other

types of kit. A commercially made PCB and ceramic valve socket gives a

professional look to the electronic part of the set. The output transformer

is a small 220 to 6V type. Turns ratio is 36.7. If the headphones are 8R

(two 16R in parallel), the reflected impedance is close to 11k. The headphone

socket is a stereo 3.5mm type with both channels in parallel.

I initially wasn't too keen on the tuning

capacitor mounted on the plastic panel, since there would be nothing to

shield it from hand capacitance. Ideally the front panel would be metal

of some sort, and earthed. Also, the wires to the regeneration pot were

longer than I'd like (I'm too used to VHF!) and I wondered how stable the

set would be in operation.

The first power up was disappointing. The two 50kW ABC stations were barely audible, and required critical adjustment. Connecting the outdoor aerial was necessary, and to start with I did that by connecting to the active end of the aerial coil by about 10pF of capacitance. This brought up the volume, but the set was difficult to tune, with the hand capacitance evident. It was impossible to tune above about 800kHz, but instead was able to tune to one of the airport beacons on 347kHz. Something was not right with the tuned circuit. Either the capacitance or inductance was too high.

First thing was to check the tuning condenser.

I discovered the wires were reversed for the fixed and moving plates, which

would have made the hand capacitance effect worse. I noted the trimmer

capacitor adjustment had no effect.

The particular tuning capacitor supplied

appears to be for a MW/SW and VHF type of set. There are two sections of

6-278pF and another two of 6-17pF. Not surprisingly for this set, only

one of the 278pF sections is used. I noted that the trimmer capacitors

had separate terminals which is why they had no effect. But why could it

not tune up to the high frequency end of broadcast band? That leaves the

aerial coil, and this was where the surprise was lurking.

Unsuitable Aerial Coil.

I was rather surprised to find the aerial

coil measured 906uH. For a MW set, it should be a fraction of that; somewhere

around 200uH. Maybe it was something to do with the ferrite rod itself.

I tried another rod in the coil and the result was much the same.

Calculating the resonant frequency, it was obvious what the problem was. With a 270pF capacitor and a 906uH coil, the frequency is 322kHz. No wonder it received the LW airport beacons and not the upper end of the broadcast band. A further calculation revealed the coil needed to be reduced to about 330uH, for 530kHz to be the lowest frequency. The only thing to do now was start removing turns. With 47 turns removed, the inductance was now 343uH. The set now tuned the complete broadcast band. The final thing was a proper external aerial connection. I simply wound 13 turns on the other end of the ferrite rod and added a set of terminals. A separate primary coil is preferable to a capacitive coupling, since the loading of the aerial has less effect, and the gain is more consistent across the band. In the introductory photo, you can see the lesser amount of coil turns on the modified receiver, and the new primary coil, and terminals. I would have liked to use Fahnestock clips for the terminals, but unless you live inside the U.S. they cost a small fortune. I used spring speaker terminals instead.

With that done, the receiver was working

very well. The regeneration control is very smooth with no backlash. Overall

performance is much the same as the 1Q5 receivers. Hand capacitance is

not a problem, and even distant stations can be easily tuned, without it

going off frequency when the hand is removed from the tuning knob. The

PCB has 9-18V printed on the B+ terminal. I found no difference between

9 and 18V, except the regeneration point is slightly different.

One has to wonder how many people have

been caught out with the incorrect aerial coil, and worse still how many

didn't know it was an easy fix? And, why was it wound for such a high inductance

in the first place?